For long-distance transportation within the cell, RNA molecules rely on hitchhiking.

A microscopic RNA molecule might need to travel as far as a meter to get from the nucleus of a nerve cell to its tip, where it’s needed to make a protein. But exactly how RNA gets around has been “a long-standing question in the field”—and one with big implications for how cells work, says Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, a senior group leader at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Reseach Campus.

Now, she and her colleagues, including co-senior author Michael Ward at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, have found one explanation: RNA molecules hitch a ride on structures called lysosomes, best known for their role as cellular recycling centers, the team reports September 19, 2019, in the journal Cell.

This transit might go awry in people with the neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the work suggests.

RNA transportation is a key part of keeping a cell functioning properly. RNA carries instructions for building proteins. Often, it’s dispatched to wherever the protein it codes for is needed, then translated into a protein on-site. So if RNA isn’t distributed around a cell correctly, key proteins might not end up in the right places. That’s a particularly big deal in large cells like neurons.

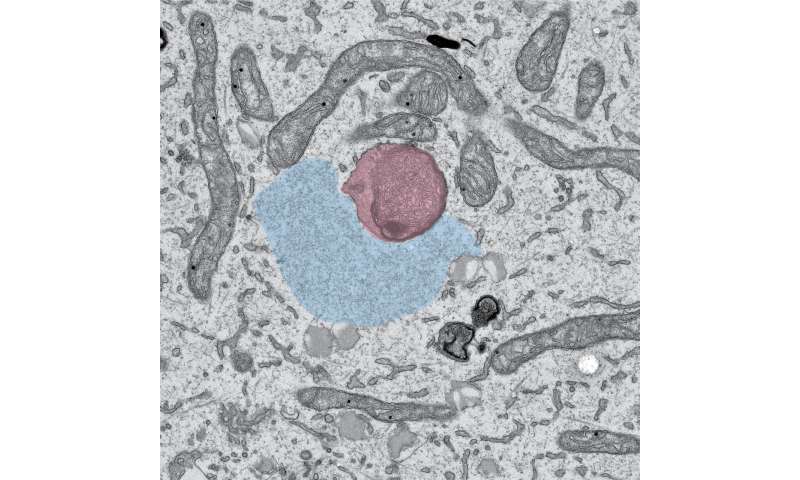

In a healthy neuron, RNA molecules cluster together with proteins to form “granules,” packets of RNA that can be ferried around more easily than individual RNA strands. Then, a protein called Annexin A11 works like a power adaptor, Lippincott-Schwartz, Ward, and their colleagues showed. It can latch onto both standard membrane-bound organelles, like lysosomes, and membraneless structures, like the RNA granules.

Lysosomes easily zip around the cell. The adaptor protein allows RNA to take advantage of lysosomes’ mobility and plug into a transportation network that would otherwise be inaccessible.

People with ALS often have mutations in the gene for Annexin A11, says Lippincott-Schwartz. Now, it’s becoming clear how these mutations affect patients. When her team introduced mutations into the protein that mimic those seen in ALS patients, the RNA granules couldn’t attach to the lysosomes. And if RNA can’t get a ride to the places where it’s needed to make proteins, neurons might have trouble either surviving or signaling properly to other cells.

In theory, RNA granules could hitchhike on any number of organelles. But lysosomes make sense for a few reasons, says study lead author Ya-Cheng Liao, an associate at Janelia. They’re already highly mobile, moving around the cell to clean up trash. And they can pull double duty: Once the RNA has been deposited at its destination to be translated, the lysosome can perform its traditional function of taking up and digesting molecules from its surroundings.

“You can think of this paper as defining a new function for lysosomes,” says Lippincott-Schwartz.

Source: Read Full Article