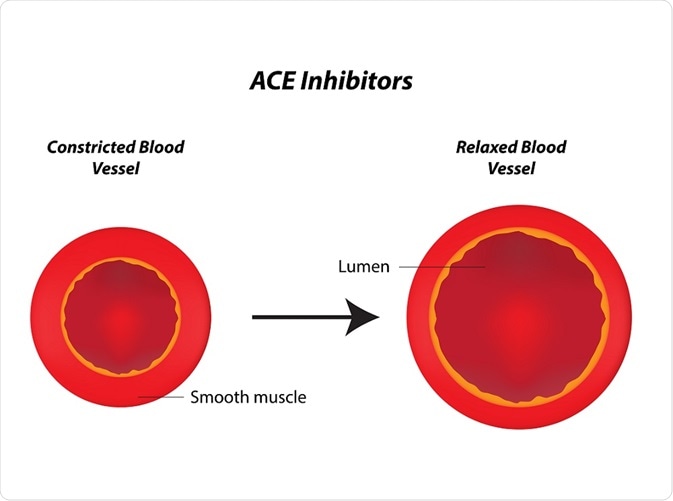

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are drugs used to treat high blood pressure and congestive heart failure. They are also used to prevent kidney disease in certain patients. These drugs dilate the blood vessels and lower the blood pressure by inhibiting the actions of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), an enzyme that helps regulate blood pressure.

Skip to:

- How do ACE inhibitors work?

- Examples of ACE inhibitors

- Common side effects of ACE inhibitors

- ACE Inhibitor Precautions

- ACE Inhibitors in Heart Failure

- ACE Inhibitors and Acute Kidney Injury

- ACE Inhibitors and Diabetes

- ACE Inhibitors in Hyperkalemia

- ACE Inhibitors and Creatinine

- Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) versus ACE inhibitors

Image Credit: joshya / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: joshya / Shutterstock.com

How do ACE inhibitors work?

ACE inhibitors and the RAAS system

ACE inhibitors work by interfering with the body’s renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). RAAS is a complex system responsible for regulating the body's blood pressure. The kidneys release an enzyme called renin in response to low blood volume, low salt (sodium) levels or high potassium levels. Angiotensinogen, which is synthesized in the liver, is the main substrate for renin.

Renin catalytically cleaves these circulating angiotensinogen and forms angiotensin I. Angiotensin-converting enzymes then convert angiotensin I to its physiologically active form, angiotensin II. Angiotensin II causes contraction of the muscles surrounding blood vessels, effectively narrowing vessels and increasing blood pressure. It also stimulates the release of aldosterone, which stimulates water and sodium reabsorption, thereby, increasing blood volume and blood pressure.

ACE inhibitors stimulate the dilation of blood vessels by inhibiting the production of angiotensin II. The major organs that ACE inhibitors affect are the kidney, blood vessels, heart, brain, and adrenal glands. The inhibitory effects lead to increased sodium and urine excreted, reduced resistance in kidney blood vessels, increased venous capacity, and decreased cardiac output, stroke work, and volume.

ACE inhibitors and bradykinin

ACE is also involved in the breakdown of bradykinin, a vasodilator. ACE inhibitors block the breakdown of bradykinin, causing levels of this protein to rise and blood vessels to widen (vasodilation). Increased bradykinin levels are also responsible for the most common side effect of ACE inhibitor treatment; a dry cough.

Examples of ACE inhibitors

ACE inhibitors are classified as either short-acting or long-acting, depending on their duration of action. Both can be effective therapy options; however, long-acting ACE inhibitors offer the advantage of less frequent dosing. For example, Lisinopril is a long-acting ACE inhibitor which needs to be taken once a day, whereas Captopril is a short-acting ACE inhibitor which has to be taken thrice daily.

Other examples of ACE inhibitors include:

- Benazepril,

- Fosinopril,

- Lisinopril,

- Captopril,

- Enalapril,

- Ramipril,

- Moexipril,

- Quinapril,

- Trandolapril.

An appropriate ACE inhibitor can be selected after considering the patient’s health and the condition to be treated.

Common side effects of ACE inhibitors

ACE inhibitors are a fairly well-tolerated class of drugs and produce only a few side effects. Common side effects of this class of drugs include:

A dry, irritating cough

This is one of the most common side effects reported in patients who have been prescribed ACE inhibitors. It is caused by the accumulation of inflammatory compounds such as bradykinin and substance P, the release of which is stimulated by ACE inhibitors.

Dry coughs occur in almost 1 in 10 patients on ACE inhibitors and it can take 8 – 12 weeks for the cough to disappear once the medication is discontinued. This effect occurs with all ACE inhibitors, so changing to a different ACE inhibitor type is unlikely to provide any relief.

Light-headedness and dizziness

ACE inhibitors only offer modest improvements in blood pressure for most patients, hence, light-headedness and dizziness are rarely reported. These effects are more prominent in patients with hypotension (very low blood pressure). Hypotension is frequently observed in patients with heart failure; thus, caution is needed when beginning or changing ACE inhibitors in at-risk patients.

Hyperkalemia (elevated potassium levels in the blood)

Aldosterone is a hormone that regulates the excretion of potassium in the kidneys via urine. ACE inhibitors lower the levels of aldosterone, thereby promoting potassium retention in the kidneys and bloodstream.

People with diabetes and kidney disease are at increased risk of hyperkalemia so ACE inhibitors must be used with caution in these patients. Symptoms of hyperkalemia include: general weakness, confusion, and muscle cramps. In severe cases, hyperkalemia can lead to dangerous cardiac arrhythmias (an abnormal heartbeat).

Angioedema (swelling under the skin)

Angioedema is the most severe symptom associated with ACE inhibitors and occurs in 0.1-0.2% of patients. Airway swelling and obstruction due to the accumulation of fluid (and bradykinin) are the main features of angioedema. The severity of the condition depends on which area is affected.

Mild angioedema is may appear as temporary swelling in the lips, tongue, or mouth. In severe cases, where the upper airway and larynx are affected, patients may have difficulties breathing and emergency care may be required. Patients experiencing angioedema while using an ACE inhibitor must discontinue the medication and avoid all ACE inhibitors in the future.

Dysgeusia (an abnormal taste in the mouth)

Dysgeusia is a common side effect of ACE inhibitors. Due to the presence of a sulfhydryl moiety, Captopril is often associated with a metallic taste. These effects, however, tend to disappear with prolonged use.

Renal impairment

Renal insufficiency occurs commonly in patients with severe bilateral renal artery stenosis who initiate ACE inhibitor use. This problem occurs because ACE inhibitors inhibit efferent renal arteriolar vasoconstriction which, in turn, lowers the filtration rate of the kidney. These effects can be reversed by discontinuing the drug.

Other side effects

- Vomiting and diarrhea – If severe, vomiting and diarrhea may lead to dehydration, which can lead to hypotension (dangerously low blood pressure).

- Fatigue, headaches, fainting, weakness and sexual dysfunction are rare side effects that have been associated with the use of ACE inhibitors.

Image Credit: SZ Photos / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: SZ Photos / Shutterstock.com

ACE inhibitor precautions

Although ACE inhibitors are very useful for treating several diseases, they are not recommended in patients who have experienced an extreme reaction in the past. ACE inhibitors are not recommended in patients who have a previous history of angioedema or hypersensitivity to this class of drugs. Hypersensitivity reactions due to ACE inhibitors are characterized by severe airway swelling (angioedema), which can be life-threatening if the respiratory pathways are affected.

Interactions of ACE inhibitors with other drugs

Concomitant use of ACE inhibitors with a diuretic or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is discouraged, as these combinations increase the risk of kidney injury. NSAIDs constrict the blood vessels that supply the kidneys. Similarly, diuretics reduce blood volume and decrease blood flow to the kidneys.

The kidneys can compensate for this loss in blood flow using the renin-angiotensin system (RAAS), however, ACE inhibitors target the RAAS, meaning the kidneys are unable to recover. This severely lowers blood pressure, increasing the risk of acute kidney injury. ACE inhibitors are therefore not recommended for patients with renal artery stenosis.

Dehydration

Individuals who suffer from dehydration due to the use of chronic diuretic therapy or poor glycemic control (diabetes) are often dehydrated. In these patients, ACE inhibitors are only prescribed at very low doses to prevent rapid and dangerous hypotension (low blood pressure).

Pregnancy

ACE inhibitors are not recommended in women who are in their second or third trimester of pregnancy due to an increased risk of fetal kidney damage and congenital disabilities such as limb deformities and cranial ossification.

Potassium supplementation

ACE inhibitors have been associated with hyperkalemia (increased blood potassium levels); hence, potassium supplementation should be avoided when taking this medication.

ACE inhibitors in heart failure

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system plays a vital role in the development of congestive heart failure (CHF). ACE inhibitors are commonly prescribed for heart failure as they have been shown to improve symptoms, reduce the duration of hospital stay, and improve survival.

ACE inhibitors relieve heart failure symptoms, such as fluid build-up and swelling, by the load on the heart. They reduce the symptoms of fatigue and shortness of breath and also increase exercise capacity.

ACE inhibitors and acute kidney injury

ACE inhibitors are the most common drugs used for hypertension and heart failure. However, even patients with a normal renal function who are treated with this drug are at an increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI).

The propensity to develop AKI is more common in situations associated with decreased glomerular filtration pressure, such as diuretic therapy or dehydration. However, AKI can develop shortly after initiation of ACE inhibitor therapy or can develop after months or years of treatment.

Temporary cessation of ACE inhibitors is recommended in patients with dehydration, hypotension, or deteriorating renal function.

ACE inhibitors and diabetes

Diabetic nephropathy is a condition that occurs in diabetes when the kidney becomes damaged by high blood glucose levels. Diabetic nephropathy stops the kidneys from being able to filter out proteins from the water to be excreted, resulting in proteinuria (proteins in urine). Diabetic nephropathy can progress to kidney failure if not carefully managed.

Blood pressure control and blood glucose control are key to avoiding diabetic nephropathy and its complications. ACE inhibitors are known to reduce the likelihood of progression to end-stage kidney disease, so are not typically prescribed for patients with diabetic nephropathy.

ACE inhibitors and high potassium levels (hyperkalemia)

Hyperkalemia is frequently observed after treatment with angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitors. The condition may range from mild and asymptomatic to life‐threatening. The effect is prominent in patients with diabetes, heart failure, and pre-existing kidney disease. Common signs of hyperkalemia include cardiac dysrhythmias, weakness, confusion, muscle cramps, and shortness of breath.

Before initiating ACE inhibitor therapy, it is essential that kidney function tests are carried out. These assessments help doctors to identify patients at increased risk of adverse events so that they can prescribe a low dose at first and build up the dosage over time, whilst monitoring potassium levels in the blood.

A low‐potassium diet and the use of diuretics that increase potassium elimination may also reduce the incidence of hyperkalemia.

ACE inhibitors and creatinine

Treatment with ACE inhibitors is associated with an acute increase in serum creatinine; a sign of mild kidney damage. Increased creatinine levels are attributed to the decline in the blood pressure in the kidney, caused by the inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system. The rise in creatinine levels is associated with a higher risk for end-stage renal disease, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

Generally, ACE inhibitors should be discontinued if the serum creatinine levels increase by 30% or more.

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) versus ACE inhibitors

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or angiotensin II receptor antagonists, are medications that lower blood pressure by blocking angiotensin receptors and altering the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). They are mainly used in the treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetic kidney disease and congestive heart failure.

Angiotensin II is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and increases blood pressure. The hormone is implicated in the pathogenesis of conditions such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, and renal diseases. ARBs bind to the angiotensin II receptors and hence inhibit the actions of angiotensin II.

Blocking angiotensin II receptors produces almost the same outcome as the ACE inhibitors, but ARBs are associated with fewer side effects. The development of a dry cough and angioedema, two important side effects of ACE inhibitors do not occur with ARBs. However, ARBs have been less well studied, and there is stronger evidence to support the use of ACE inhibitors over ARBs. ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be used simultaneously.

ARBs are well absorbed after oral administration and are available in tablet form. Common side effects include dizziness, hyperkalemia, and headache, while less common side effects include diarrhea, liver dysfunction, back pain, muscle cramp, renal impairment, and nasal congestion.

Sources

- Hsu, F. Y. et al. (2017). Renoprotective Effect of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers in Diabetic Patients with Proteinuria. Kidney Blood Press Res. doi.org/10.1159/000477946.

- Raebel, M. A. (2011) Hyperkalemia Associated with Use of Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. Cardiovascular Therapeutics. doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00258.x.

- NIH. (2017) Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors. livertox.nih.gov/Angiotensin-Converting_Enzyme_Inhibitors.htm.

- American College of Cardiology. ACE/ARB Therapy for Patients (Inpatient and Outpatient Setting). www.acc.org/tools-and-practice-support/clinical-toolkits/heart-failure-practice-solutions/ace-arb-therapy-for-patients-inpatient-and-outpatient-setting.

- Corbo, J. et al. (2016). ACE Inhibitors or ARBs to Prevent CKD in Patients with Microalbuminuria. American Family Physician. www.aafp.org/afp/2016/1015/p652.html.

- Michael, R. 2014. The JNC 8 Hypertension Guidelines: An In-Depth Guide. AJMC. www.ajmc.com/journals/evidence-based-diabetes-management/2014/january-2014/the-jnc-8-hypertension-guidelines-an-in-depth-guide.

- Bratsos, S. (2019). Efficacy of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitors in the Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure: A Review of Landmark Trials. Cureus. 10.7759/cureus.3913.

Further Reading

- All ACE Inhibitors Content

Last Updated: Jan 13, 2021

Source: Read Full Article