When we walk through the doors of a hospital, as a patient we expect to receive the best care that is medically available.

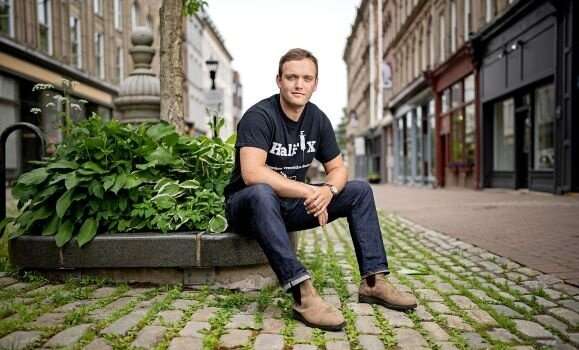

Dr. Thomas Brothers, a Dalhousie University general internal medicine resident, has taken a deep dive into addiction treatment and harm reduction services at the Saint John Regional Hospital and the QEII and results show there is room for improvement.

The manuscript, “Unequal access to opioid agonist treatment and sterile injecting equipment among hospitalized patients with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis” (IDU-IE), was recently published in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed open-access scientific journal produced by the Public Library of Science. Dr. Brothers and his colleagues, including Dalhousie faculty in both Halifax and New Brunswick, gathered hospital data over an 18-month period between 2015–2017 and found that patients with IDU-IE in the Canadian Maritimes have unequal access to addiction care depending on where they are hospitalized, which also differs greatly from the community-based standard of care.

The study was inspired by a desire to identify how people were being admitted to hospital with IDU-IE and how many were offered appropriate care. While Dr. Brothers was completing his medical school training at Dalhousie, he noted the frequency with which patients were admitted with serious, life-threatening bacterial infections such as endocarditis resulting from injection drug-use. The pattern following these admissions alerted him to the need to help these patients.

“They would not do very well,” he recalls. “They would present in serious pain and withdrawal and would often leave the hospital to get drugs to treat their symptoms, and it seemed like nobody really knew how to help.”

An alarmingly high 10–20% of patients on the internal medicine ward are there with medical complications from addiction. Traditionally, the focus has been on medical treatment: antibiotics for bacterial infections, diuretics for those with liver disease or heart failure from alcohol, and consultations with social work to offer counseling and other supports. In Halifax, addiction treatment in hospital with evidence-based medications simply was not available.

A community of care

While witnessing the hospital situation, Dr. Brothers was completing electives at local harm reduction organizations such as Mobile Outreach Street Health (MOSH) and Mainline Needle Exchange. It was at MOSH that he met founder Patti Melanson, a registered nurse and co-author on the paper, who introduced him to compassionate, expert harm reduction care in the community. What they offered was so drastically different from what was available in hospital that Dr. Brothers set out to determine how to incorporate what was provided in the community into acute care settings.

He was subsequently introduced to Dr. Duncan Webster, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine, and an infectious disease specialist in New Brunswick, who had been providing addiction and harm reduction care to hospitalized patients in Saint John since the early 2000s. Dr. Webster initiated the program after a troubling hospital encounter with a young woman with endocarditis, eager for opioid addiction treatment with methadone and with no availability at the local outpatient clinics for six months.

“I can remember her comment to me was, “So you’re gonna throw me back to the wolves,'” says Dr. Webster. “There were just so many obvious gaps in the system.”

Dr. Webster and his team in the Division of Infectious Diseases began offering patients opioid agonist treatment (OAT; e.g. methadone, buprenorphine) and access to sterile drug injecting equipment in hospital with continued care upon discharge into the community.

Learning of this program, Dr. Brothers was motivated to adopt something similar in Nova Scotia.

“If they’re doing this in Saint John, why can’t we do this in Halifax?”

Disparities in care

In 2017, Dr. Brothers and his team, in consultation with addiction support providers in the community and in hospital, began to gather data to establish a baseline for what was happening and determine where things could be improved. Results showed that OAT was offered to 36% of patients suffering from IDU-IE in Halifax, and 100% of patients in Saint John. Once patients were offered this care, most initiated and planned to continue OAT after discharge. In Halifax, no patients were offered sterile injection equipment, while several patients were offered this in Saint John.

The team also used the data to identify descriptions of unmet care needs documented in the medical records of patients with IDU-IE at each hospital. They found this often included undertreated pain or opioid withdrawal, illicit/non-medical drug use in hospital, and patient-initiated discharges against medical advice. Several patients at both hospitals had their belongings searched and had their own injecting equipment confiscated, despite the existing policy in Saint John.

An opportunity for change

Dr. Brothers, who is part of the Clinician Investigator Program at Dalhousie, as well as a Ph.D. candidate at University College London (both while he finishes his subspecialty training in general internal medicine and addiction medicine), worked with his colleagues using the data to make a case for change. Their recommendations include: employment of healthcare providers with addiction medicine expertise by the hospitals, as well as the development of harm reduction-oriented policies to promote patient safety. As is the case in Saint John, hospital-based addiction care could be improved through integrating addiction medicine and infectious diseases specialist practice, or through establishing specialized addiction medicine consultation services and incorporating these providers into multidisciplinary endocarditis care teams.

Recommendations aside, Dr. Webster says that it’s great to see change in the culture, attitudes, and understanding around opioid agonist treatment and the harm reduction approach.

“For a lot of the clinical people who weren’t so sure about it initially, now there’s not even a discussion and it’s just taken as, “Yes this works, and this is the way to do it.'”

What has transpired over the last several years is the commitment of both hospitals to work on improving their policies for supporting people who use drugs and people with addiction while they’re in hospital. In Saint John, they continue to offer harm reduction services to patients, and they have improved their inpatient needle exchange program and provide sterile equipment routinely. In Halifax, an unofficial, trainee-organized, hospital addiction medicine consultation service staffed by residents and supervised by Dr. John Fraser, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry, and other community-based addiction physicians, provides care in an area that remains without a formal complement of staff. Dr. Brothers, who helped lead this initiative received recognition for his work with the Canadian Medical Association’s 2021 Award for Young Leaders, but knows more is needed.

“We’re providing this care informally to fill the gap while we’re advocating for a formal service so we can have specialist addiction medicine providers available in the moment, everyday, seeing patients, managing withdrawal, offering medications, and doing counseling.”

The way forward

Progress, whether formal or not, has been made, but Dr. Brothers knows there is more work to do. He would like to see the hospitals work more closely with harm reduction organizations, who are leaders in the field, to incorporate their expertise into a model of care.

Source: Read Full Article