New UBC research shows that midwives in British Columbia are providing safe primary care for pregnancies of all medical risk levels, contrary to a popular belief that midwives mostly manage low-risk pregnancies.

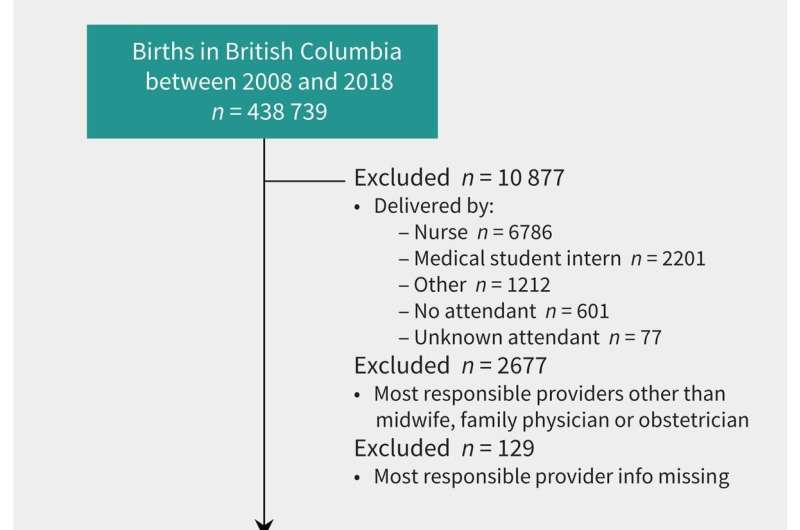

The study, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, examined a decade of births in B.C. between 2008 and 2018. The researchers compared birth outcomes for people who had a midwife as their most responsible provider (MRP), with those who were cared for by a family physician or obstetrician.

The findings reveal that people who had a midwife as their MRP had comparable or improved birth outcomes relative to family physician- or obstetrician-led care across medical risk levels. Midwifery clients were less likely to have preterm births and low-birth-weight babies compared to physician-led care, and the risk of infant death was comparable across MRPs.

“The study provides evidence that midwifery care in B.C. is a safe and effective option for childbearing people, regardless of medical risk,” said Dr. Kathrin Stoll, a research associate in UBC’s department of family practice. “As medical risk increases, midwives and family physicians collaborate with obstetrician specialists to ensure that birthing people are receiving safe and appropriate care that is right for them.”

The researchers say the findings are a reflection of how midwives are integrated into B.C.’s health system.

“Midwives operate in two worlds: They are in the community working with people in their homes, but they are also integrated into the hospital system,” said Dr. Stoll. “When complications develop, midwives are a bridge to the specialist and hospital care that a person needs.”

Midwifery clients also had consistently lower cesarean delivery rates compared to people with physician MRPs, although the rate of cesarean delivery increased as medical risk increased. Close to 37 percent of births in B.C. were cesarean deliveries in 2019-2020, the highest in the country.

The changing face of midwifery care

The new study shows how midwifery care in B.C. has evolved since it became a regulated health profession in 1998.

The proportion of births that had a midwife MRP increased from 9.2 percent in 2008 to 19.8 percent in 2018. That proportion has continued to climb in more recent years, with midwives now assisting with nearly a third of all births in B.C.—the highest proportion in Canada.

The profile of midwifery clients is also changing.

“Whereas midwifery care may have started out primarily with low-risk clients, the study provides evidence that the profile of clients is changing and that midwives are increasingly caring for clients safely at all medical risk levels,” said Dr. Stoll.

The researchers say they were not surprised by the findings because medical risk has always been a core part of the profession.

“A large part of midwifery education is teaching students about medical complexities and how to triage clients in terms of their medical risk. It’s always been a part of midwifery training and the care midwives provide,” says Dr. Luba Butska, an assistant professor of teaching with UBC’s midwifery program in the department of family practice.

Despite increases in midwifery care during the study period, Canada has some of the lowest rates of midwifery access in the world and increasing rates of cesarean delivery.

The study recommends that the growing midwifery profession should be supported by policies and payment structures that enable retention of midwives, and by health system integration and collaboration with physician colleagues.

“As the midwifery profession continues to grow in Canada, it holds potential for meeting national mandates to lower obstetric intervention rates and to increase access to midwifery care to under-served communities,” said Dr. Butska. “It’s the combination of good outcomes and lower intervention rates that make midwifery a great public health strategy.”

More information:

Kathrin Stoll et al, Perinatal outcomes of midwife-led care, stratified by medical risk: a retrospective cohort study from British Columbia (2008–2018), Canadian Medical Association Journal (2023). DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.220453

Journal information:

Canadian Medical Association Journal

Source: Read Full Article