A trio of researchers were awarded the Nobel Medicine Prize on Monday for their discovery of the Hepatitis C virus, paving the way for blood tests and new treatments.

Thanks to their work the disease is now largely curable. Yet there are more than 70 million people living with the virus, the vast majority of which are not diagnosed.

400,000 deaths

Unlike Hepatitis A, which is spread via polluted food or water, Hepatitis C is a blood-borne pathogen that causes liver diseases such as cancer and cirrhosis.

Patients can often be infected for years—sometimes decades—without showing symptoms, making Hepatitis C difficult to diagnose until infection gets serious.

Its effects can range from illness lasting a few weeks to life-long medical conditions.

The World Health Organization says Hepatitis C kills around 400,000 people a year, although that is likely to be an underestimate as many patients die from liver failure before they are diagnosed.

In all, hepatitis viruses kill more than a million people every year, putting it on a par with other global health threats such as HIV and tuberculosis.

Incidence is especially high in the Eastern Mediterranean and Europe, according to the WHO.

The most common modes of infection are sharing needles, blood transfusions, unsafe healthcare or unprotected sex.

New treatments

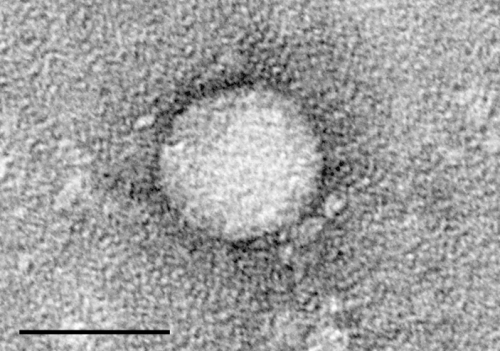

Americans Harvey Alter and Charles Rice together with Briton Michael Houghton were honoured for discovering the Hepatitis C virus, which is distinct from two other viral strains, A and B.

Their work allowed the rapid development of antiviral drugs and blood tests, although there is no vaccine against Hepatitis C.

Around 80 percent of people exposed to the virus develop chronic conditions, particularly cirrhosis—scarring of the liver, which can lead to organ failure.

For years treatment for Hepatitis C was only moderately effective—curing roughly half of patients—and came with a string of undesirable side effects.

But a new generation of drugs known as direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have seen success rates soar, with around 95 percent of patients who are treated being cured.

Unequal access

However new treatment regimens remain prohibitively expensive in many regions.

In 2017, the WHO estimated that just 19 percent of those infected globally received a diagnosis. Fewer than 10 percent received DAAs.

The Nobel committee said Monday that the world could for the first time eradicate Hepatitis C.

“To achieve this goal, international efforts facilitating blood testing and making antiviral drugs available across the globe will be required,” it said.

Source: Read Full Article