Contrary to what has been generally assumed so far, a severe course of COVID-19 does not solely result in a strong immune reaction—rather, the immune response is caught in a continuous loop of activation and inhibition. Experts from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the University of Bonn, the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), along with colleagues from a nationwide research network, present these findings in the scientific journal Cell.

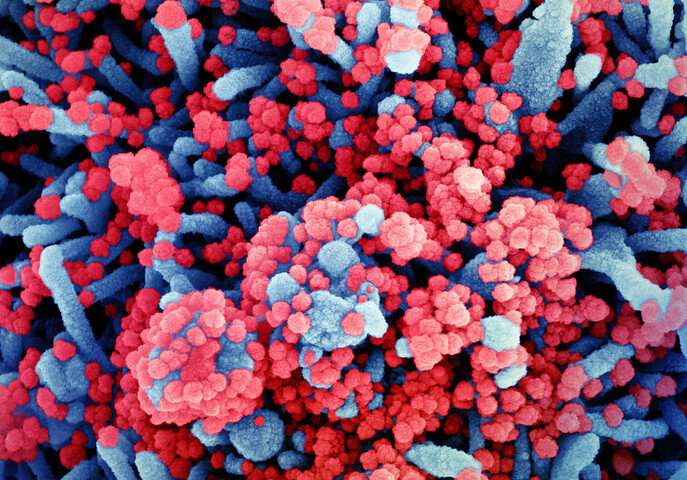

Most patients infected with the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 show mild or even no symptoms. However, 10 to 20 percent of patients develop pneumonia during the course of COVID-19 disease, some of them with life-threatening consequences. “There is still not very much known about the causes of these severe courses of the disease. The high inflammation levels measured in those affected actually indicate a strong immune response. Clinical findings, however, rather indicate an ineffective immune response. This is a contradiction,” says Joachim Schultze, professor at the University of Bonn and research group leader at the DZNE. “We therefore assumed that immune cells are produced in large quantities, but that their function is defective. Therefore, we analyzed the blood of patients with varying degrees of COVID-19 severity,” explains Leif Erik Sander, Professor of Infection Immunology and Senior Physician at Charité’s Medical Department, Division of Infectious Deseases and Respiratory Medicine.

High-precision methods

The study was carried out within the framework of a nationwide consortium—the “German COVID-19 OMICS Initiative” (DeCOI) – meaning that the analysis and interpretation of the data being spread across various teams and sites. Joachim Schultze was significantly involved in coordinating the project. The blood samples came from a total of 53 men and women with COVID-19 from Berlin and Bonn, whose course of disease was classified as mild or severe according to the World Health Organization classification. Blood samples from patients with other viral respiratory tract infections as well as from healthy individuals served as important controls.

The investigations involved single-cell OMICs technologies, a collective term for modern laboratory methods used to determine, for example, the gene activity and the amount of proteins on the level of individual cells—thus with very high resolution. Using this data, the scientists characterized the properties of immune cells circulating in the blood—so-called white blood cells. “Applying bioinformatics methods to this very extensive data set of the gene activities of each individual cell, allowed us to gain a comprehensive view of the activities of white blood cells,” explains Yang Li, Professor at the Centre for Individualized Infection Medicine (CiiM) and Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in Hannover. “Combining sequencing with the detection of important proteins on the surface of the immune cells, allowed us to decipher the changes in the immune system of patients with COVID-19,” adds Birgit Sawitzki, Professor at the Institute of Medical Immunology on Campus Virchow-Klinikum.

“Immature” cells

The human immune system comprises a broad arsenal of cells and other defense mechanisms that interact with each other. In the current study, the focus was on so-called myeloid cells, which include neutrophils and monocytes. These are immune cells that are at the very front of the immune response chain, i.e. they are mobilized at a very early stage to defend against infections. They also influence the later formation of antibodies and other cells that contribute to immunity. This gives the myeloid cells a key position.

“With the so-called neutrophils and the monocytes we have found that these immune cells are activated, i.e. ready to defend the patient against COVID-19 in the case of mild disease courses. They are also programmed to activate the rest of the immune system. This ultimately leads to an effective immune response against the virus,” explains Antoine-Emmanuel Saliba, head of a research group at the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI) in Würzburg.

But the situation is different in severe cases of COVID-19, explains Sawitzki: “Here, neutrophils and monocytes are only partially activated and they do not function properly. We find considerably more immature cells that have a rather inhibitory effect on the immune response.” Sander adds: “The phenomenon can also be observed in other severe infections, although the reason for this is unclear. Many indications suggest that the immune system stands in its own way during severe courses of COVID-19. This could possibly lead to an insufficient immune response against the corona virus, with a simultaneous severe inflammation in the lung tissue.”

Approaches to therapy?

The current findings could point to new therapeutic options, says Anna Aschenbrenner from the LIMES Institute at the University of Bonn: “Our data suggest that in severe cases of COVID-19, strategies should be considered that go beyond the treatment of other viral diseases.” The Bonn researcher says that in the case of viral infections one does not actually want to suppress the immune system. “If, however, there are too many dysfunctional immune cells, as our study shows, then one would very much like to suppress or reprogram such cells.” Jacob Nattermann, Professor at the Medical Clinic I of the University Hospital Bonn and head of a research group at the DZIF, further explains: “Drugs that act on the immune system might be able to help. But this is a delicate balancing act. After all, it’s not a matter of shutting down the immune system completely, but only those cells that slow down themselves, so to speak. In this case these are the immature cells. Possibly we can learn from cancer research. There is experience with therapies that target these cells.”

Nationwide team effort

Source: Read Full Article