As President Joe Biden promises to vaccinate more than 100 million Americans by the end of his first 100 days in office (April 29), new research offers several critical insights for those in charge of managing such a massive national public health effort.

The researchers, who hail from four major U.S. universities, including Northwestern University, surveyed approximately 25,000 people from around the nation between Dec.16, 2020, and Jan. 10. They accounted for participants’ race, gender, age, education, political affiliation and where they lived. Their findings show Americans:

- Generally favor getting a vaccination themselves (75%)

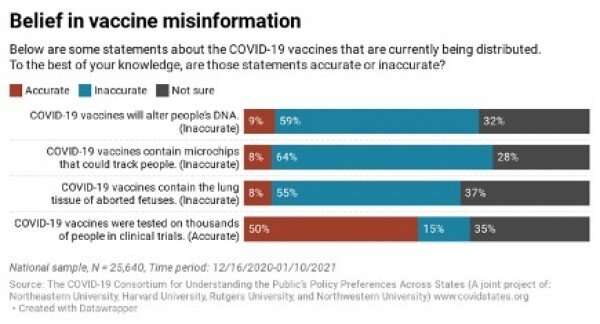

- Do not typically believe COVID-19 vaccine misinformation, though certain groups are more likely to believe false information about vaccines

- Are more likely to be swayed to get vaccinated by messages from their doctors and scientists than those from famous political figures, athletes or actors

- Generally agree with current policies prioritizing which groups should get vaccinated first, such as frontline medical personnel and first responders

“These are promising findings as there is less vaccine resistance than many anticipated; it also accentuates that despite the politicization of science during COVID-19, individuals from both parties remain trustful of their physicians and scientists more generally,” said James Druckman, the Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science and Institute for Policy Research associate director. Druckman is part of a university research consortium, which includes Northwestern, Harvard, Northeastern and Rutgers, investigating attitudes on COVID-19.

Most respondents agreed with putting medical professionals, first responders and those at greatest medical risk from COVID-19 at the front of the line for vaccines. These are the same groups at the top of current implementation plans.

More are vaccine ‘hesitant’ than vaccine ‘resistant’

In addition to asking standard questions about how likely a person was to get vaccinated (from “least” to “most likely”), the researchers also asked when a person would prefer to be vaccinated (with four possible responses from “as soon as possible” to “never”). This second question allowed the researchers to identify who is just vaccine “hesitant,” or would agree to get the vaccine at some point, from those who are vaccine “resistant,” defined as those who would never get a vaccine at any point.

Their results indicate that 55% of respondents said they are “extremely” or “somewhat” likely to get the vaccine, while 29% said they were “somewhat” or “extremely” unlikely to do so. Asked when they would prefer to get the vaccine, 75% said they would get it at some point—either “as soon as possible” or “after some/most people I know” got it—while 23% indicated “never.” Around 3% answered that they had already received the vaccine.

When breaking down these figures by race and ethnicity, Black respondents were the least likely to say they would get the vaccine: 33% say they would never get the vaccine when compared to White (23%), Latino (20%) and Asian (10%) respondents who said the same. This was not unexpected; previous studies have identified their mistrust as coming out of persistent inequalities in healthcare access and institutional mistreatment as exemplified by the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study in the 1930s.

By age, seniors were most enthusiastic about getting vaccinated, with the youngest group of those aged 18–24 being the least enthusiastic, perhaps due to being less affected by the virus.

Interestingly, the researchers find those most resistant to getting a vaccination were aged 25–44. In particular, parents in this age group who had children at home were the most likely of all to say that they would never get a vaccine.

The researchers find that belief in conspiracy theories about vaccines is not that widespread and that a good number of the respondents are just generally uninformed.

Vaccine messages that deliver—and the messengers who do not

In addition to asking about attitudes and beliefs around vaccinations, the researchers also ran a series of experiments that looked more closely at how best to communicate to the public about getting vaccines and those best suited to communicate to them.

To test out messages, they randomly gave respondents one of five rationales for getting vaccinated, using small written stories or “vignettes.” Researchers asked how likely a person was to get a vaccine if they were told it was their patriotic duty to do it or if their doctor had recommended it. All of the messages but one increased their chances of getting it. Those messages that discussed a physician’s or scientist’s recommendation had the largest effects, while appeals to a person’s patriotism had the smallest.

Despite the spate of famous people televised getting or recommending the vaccine, a famous person who delivers the message typically has only a slight effect on increasing a person’s desire to get a vaccine, the researchers find. Appeals by admired figures like Michael Jordan or Tom Hanks, therefore, would probably not be that helpful in encouraging people to get vaccines.

More importantly, using well-known, politically charged messengers such as Donald Trump (for Democrats) and Barack Obama (for Republicans)—as messengers could lead to more resistance. The researchers point to “out-partisan backfiring” as a likely culprit. Backfiring occurs when partisans become more, not less, resistant to a message after hearing it delivered by someone in the opposite political party.

According to the researchers, it’s who you know personally that counts the most, like doctors or friends, in convincing one to get the vaccine. Such messengers are especially effective in counties where the virus is on the rampage.

Source: Read Full Article