Jay Reinstein and Michele Hall wouldn’t seem to most people like they would be in danger of suffering from a disease typically associated with aging.

Reinstein is just 60 years old, and Hall is 54. Both of them have young adult children. Yet both already struggle with driving, and they can no longer work because their minds don’t function as they once did.

They’re two of the 200,000 Americans who suffer from early-onset Azheimer’s disease, a group of people who received crushing news Tuesday when Medicare proposed limiting their access to a potential treatment called Aduhelm meant to slow the march of their debilitating illness.

When the government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced the news, it was a bombshell for Hall, Reinstein and others like them. Despite living 700 miles apart, the two are bound together by both their earth-shattering diagnoses that forced them to quit satisfying jobs in their 50s and their quest to slow the inevitable cognitive degeneration brought on by the disease. Their greatest hope as of late was that Aduhelm, Biogen Inc.’s controversial Alzheimer’s treatment, could help enhance the quality of their still relatively young lives.

“Terrible. Horrible,” said Hall, who until 2019 was general counsel for the Manatee County Sherriff’s Office, a half-hour south of St. Petersburg, Florida, across the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. “I wasn’t prepared for that. I didn’t see it coming.”

“I’m one of the hundreds of thousands who could benefit and we can’t get it,” said Reinstein, who until a few years ago worked as an assistant city manager in Fayetteville, North Carolina. “You deflated the hope. Now what?”

All told, some 6 million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s, about half of whom the National Institute on Aging says may have mild symptoms, the target group for Aduhelm. But it’s an especially cruel blow to those in the prime of their lives. Hall and Reinstein are involved in an advocacy network for the disease that voiced its outrage over Medicare’s preliminary decision. The Alzheimer’s Association called it “shocking discrimination” that will leave only “a privileged few” the ability to get the monthly infusions of the drug.

Though younger than 65, Hall and Reinstein qualify for Medicare because of their condition. The unusual proposal not to fully cover Aduhelm reflects Medicare’s doubt that the drug will do more good than harm. The Food and Drug Administration approved the infusion last June without clear evidence it works, resulting in a firestorm of bad press and a congressional investigation. The drug also has serious side effects: headaches, dizziness, falls and even brain bleeds.

Yet despite all the drawbacks, Reinstein and Hall were eagerly awaiting their chance for treatment. When you face a future of not knowing your own grandchildren or needing help with every little task, what else are you going to do?

“I’m willing to be a guinea pig,” Reinstein said. “All we’re looking for is an opportunity.”

Reinstein and Hall met through the Alzheimer’s Association about six months ago and FaceTime every couple of weeks. Hall recently joined one of Reinstein’s support groups as well. They’re also part of an observational study called the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Study, or LEADS, funded by the National Institute on Aging, which seeks to learn more about the characteristics of cognitively impaired people ages 40 to 64.

Hall’s journey started when she was having trouble following meetings at work and finding the right words to use in conversation, but she knew something was really wrong at the doctor’s office seeking treatment for a hand injury: She looked down at the forms she was supposed to fill out and couldn’t make sense of any of it. She saw the cup of pens on the front desk and tried to focus her mind by spelling “cup.” After a half hour, she still couldn’t, and she called her husband to rush over and help.

“Oh, another thing that made it clear,” she said, then stopped and looked at her husband Doug before continuing her comments. “What was my title?”

“President of the Florida Association of Police Attorneys,” he answered, one of many times he filled in the blanks for her.

She was scheduled to give a speech at the group’s annual convention in 2019 but “nothing came to me. I decided I couldn’t work anymore.” Eventually, she got a spinal tap at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and was given the devastating diagnosis. Hall contemplated suicide and asked her law enforcement friends where to get a gun. She told her three children in their 20s that she didn’t want them to see her waste away.

“The first two or three months were really miserable,” she said. “It was hard because all the sudden you see yourself going away.”

She and Reinstein have been on an emotional roller coaster with Aduhelm. They closely followed the progress of Aduhelm through the approval process, which itself was full of ups and downs as the drug seemingly failed and then was resurrected, and then saw a rare glimmer of hope when the FDA approved the monthly infusion last year.

Hall’s husband said they’re aware Aduhelm isn’t a wonder drug, “but it could help keep her stable for six months,” he said, “then hopefully something better will come along.”

“Is it better than doing nothing? We think so,” he said.

The FDA justified Aduhelm’s approval citing the desperate need for an Alzheimer’s treatment. Even though it lacked clear benefit and carries the risk of serious side effects, Biogen priced the drug at $56,000 a year.

The company, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, slashed that price in half recently after blowback and low sales. Biogen said Tuesday that Medicare’s draft decision, which limits coverage of Aduhelm to patients in a clinical trial, will result in the majority of patients being unable to access the treatment and left “to decline without hope of intervention.” It’s not yet clear which trials will be eligible for Medicare coverage.

Aduhelm is supposed to be used only on those with mild cognitive impairment. Hall and Reinstein feared their cognitive skills could decline beyond mild before they got to try the drug.

Hall decided late last year not to wait anymore. On Dec. 29, she and her husband drove half an hour to a small infusion center in St. Petersburg, an appointment that was facilitated by the University of South Florida Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Center and Research Institute.

The needle went in her hand and the infusion lasted about an hour. She had her own room with a recliner where she watched Law & Order reruns. “Right now I feel completely fine,” she said at the start of the infusion. “We’ve been waiting for this.”

Patients begin Aduhelm on a small dose and eventually that amount is increased. The initial doses are relatively moderate in price. Hall plans to continue receiving monthly infusions for at least a couple more months. She isn’t sure how she will manage the higher costs of the increased doses if Medicare doesn’t cover them.

The government will hold a 30-day comment period for its coverage proposal and make a final determination in April. Reinstein is starting a nonprofit called Voices of Alzheimer’s that is scheduled to meet with Medicare officials in less than two weeks to try to get them to change their minds.

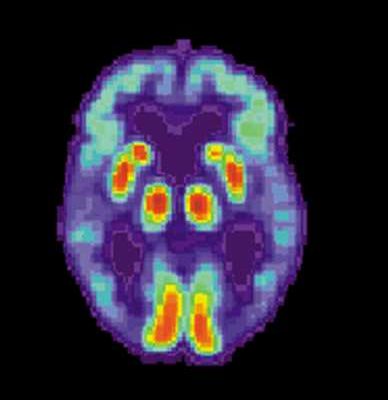

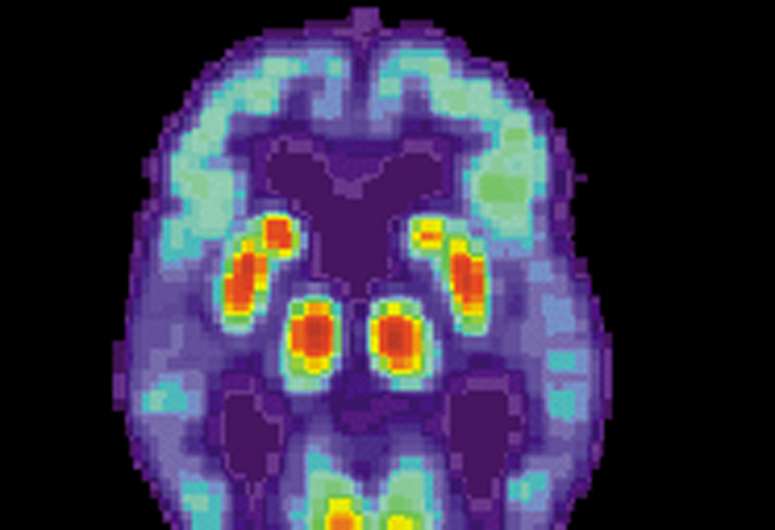

That’s a stark contrast to what he was preparing for until Tuesday’s decision. Just last week, Jay drove from Raleigh where he lives to Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., one of the locations for the LEADS study, to get a PET scan to check for the presence of abnormal protein deposits called amyloid plaque in his brain, a marker of Alzheimer’s and a requirement for receiving Aduhelm. He’ll get the results later this week and, though he isn’t sure how he’ll proceed, he desperately wants to find a way to get Aduhelm.

Jay has suffered bouts of anxiety and depression since his diagnosis about three years ago. Still, he manages to hide his distress. His outward persona is charismatic and self-effacing. He still co-hosts a weekly radio show with his friend and community activist Kevin Brooks called “Honest Conversations with Kev and Jay” on the local gospel music station in Fayetteville.

But in quiet moments it’s a different story. “A lot of worries. I wake up at night sometimes and I’m worried. I hate it.” There aren’t many resources for those with early-onset Alzheimer’s, Reinstein said, and finding people with shared experiences helps.

Source: Read Full Article