As Wayne Couzens is sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Sarah Everard, we must keep talking about how to prevent male violence against women, says Moya Crockett.

If you felt no joy at the sentencing of Wayne Couzens today – no sense of catharsis, no relief that the British criminal justice system had triumphed over evil – you’re not alone. This afternoon, Couzens was told by a judge at the Old Bailey that he will spend the rest of his life in prison for kidnapping, raping and murdering Sarah Everard, the 33-year-old woman whose disappearance and death earlier this year sparked nationwide protests about male and police violence against women.

You may also like

Sarah Everard trial: police officer Wayne Couzens sentenced to whole life sentence for her murder

Everard’s story had already broken all of our hearts, but the facts that emerged during Couzens’ two-day sentencing hearing dragged it into the realm of incomprehensible horror. Prosecutors outlined how Couzens used his status as a serving Metropolitan Police constable to falsely arrest the marketing executive, who was walking home from a friend’s house during the March lockdown when she was kidnapped.

After showing her his police warrant card, Couzens handcuffed Everard and put her in the back of his car – something he may have done on the pretext of enforcing Covid-19 restrictions. It’s impossible to hear those details without recoiling in grief, rage and disgust.

So Couzens has been sentenced to a rare whole life order, meaning he will never be eligible for parole. But despite the relatively swift progression of his case through the criminal justice system, it’s impossible to feel justice has been done. How could we feel that way, when a young woman is dead? No sentence can make up for the loss of a human life. “There is no punishment that you could receive that will ever compare to the pain you have caused us,” Katie Everard, Sarah’s older sister, told Couzens in court on Wednesday. “We can never get Sarah back.”

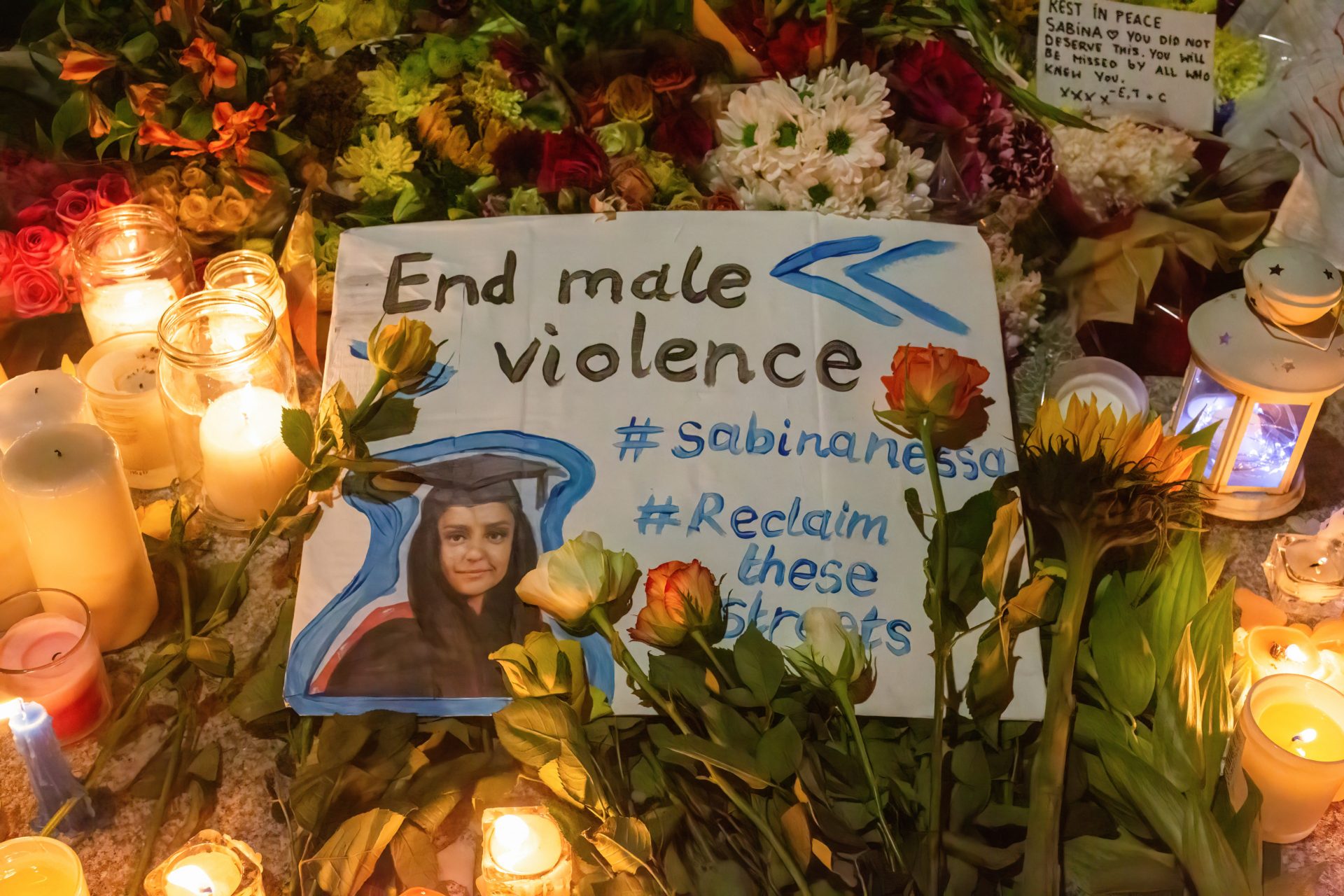

Outside the Old Bailey – the court at which, a day later, the man charged with murdering teacher Sabina Nessa would enter a not guilty plea – a Sisters Uncut protester held up a sign: “Justice means no dead women.”

Rightly, given the pivotal role Couzens’ profession played in his kidnap of Everard, debates have been reignited about how police fail to keep women safe from male violence – and can also perpetrate that violence themselves. We need to know why both Kent Police and the Met allegedly failed to investigate multiple reports that Couzens committed indecent exposure, in 2015 and 2021 respectively.

We also need to know what police forces across the country are doing to prevent violent and abusive men entering their ranks, because there’s more than just one bad apple in the barrel. New data from the Femicide Census shows that women have been killed by at least 15 serving or former police officers since 2009, while there were 308 reports of police staff perpetrating domestic abuse between April 2020 and March 2021 alone – a spike of 49% on the previous five-year average, according to data obtained by Byline Times.

Stopping male violence against women before it starts is what we really want

Some feminists – Sisters Uncut among them – believe the police will never rid themselves of violent men or prioritise the safety of women, people of colour and other marginalised groups, and should be abolished entirely as a result. But whether you’re on board with abolition or not, it is clear that we cannot rely on the criminal justice system to get to the root causes of male violence against women. Just 1.4% of reported rapes in England and Wales result in a charge or summons, while research by the domestic abuse charity Sistah Space shows that 43% of domestic abuse victims of African and/or Caribbean heritage in the UK would not feel comfortable going to the police.

Even if we could trust the police and criminal justice system to come down hard on all male perpetrators of violence against women, we would still be punishing behaviour that has already taken place – not preventing it in the first place.

You may also like

Sabina Nessa: the care and coverage given to white victims should apply to women of colour

And stopping male violence against women before it starts is what we really want. In a public consultation reopened after Everard’s murder, most of the 180,000 respondents asked the government to prioritise “more action to prevent violence against women and girls from happening”.

That doesn’t mean throwing money at better street lighting and more CCTV; it means investing in initiatives that could genuinely change the culture around male violence against women from the bottom up.

In a major multi-country study in 2013, the UN said that prevention work around male violence against women should focus on areas including “changing social norms related to the acceptability of violence and the subordination of women” and “working with young boys to address early ages of sexual violence perpetration”. These issues are not yet being adequately tackled in schools, despite the introduction of a new relationships, sex and health education (RSHE) curriculum in 2020. A recent Ofsted review found that most young people were still “rarely positive about the RSHE they had received”, while Women’s Aid has said that sex education must include a specific focus on violence against women and girls.

This isn’t the fault of teachers, who have been stretched to their limits during the coronavirus pandemic. But if teaching staff aren’t given the time and training they need to deliver these lessons effectively, we can’t expect schools to stop harmful cultural norms around male violence taking root.

You may also like

Male violence against women and girls should be as much of “an absolute priority” as countering terrorism, says report

Of course, there are millions of men who have already left school, so we also need the government to invest in other forms of prevention work. We need them to fund research into which prevention methods are most effective, with a particular focus on the safety of women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds, whose needs are often not met by mainstream services. We need culture-shifting conversations challenging the attitudes around male violence against women, which is why Stylist’s #AFearlessFuture initiative – backed by more than 60 experts including representatives of the End Violence Against Women coalition, Imkaan and Rape Crisis England & Wales – called on the government to launch a long-term, expert-informed public awareness campaign aimed directly at men.

Despite the government pledging to launch just such a campaign earlier this summer, the Home Office has yet to announce any further details, displaying a lack of urgency that is as frustrating as it is disheartening.

This is a sprawling, complex problem that resists quick fixes or easy answers

We also need individuals and institutions to commit to preventing male violence against women, and engage in genuine soul-searching when they fail to do this. This might mean investing in workplace domestic violence training, so staff can spot the signs and intervene safely if they suspect a colleague is being abused. It certainly means taking disturbing male behaviour seriously. Couzens, for example, was reportedly nicknamed “The Rapist” by colleagues at the Civil Nuclear Constabulary, because he made female colleagues so uncomfortable. We cannot continue to live in a world where intimidating male behaviour is normalised, minimised and joked about; we need other men to start challenging it when they see it.

None of this work is easy. Male violence against women is a sprawling, complex problem that resists quick fixes or easy answers. Eradicating it requires optimism, grim determination and the ability to attack the issue from all angles. But if there is any way of truly getting justice for women like Sarah Everard, Sabina Nessa, Bibaa Henry, Nicole Smallman and Joy Morgan, it’s to prioritise prevention, and work towards a world where women are no longer harmed by men. Because justice means no dead women.

Images: Getty Images

Source: Read Full Article