It was a social media post by the local sheriff that almost broke Erinn Quinn, public health director for tiny Klickitat County, Washington.

Erinn Quinn

For more than a year, Quinn and her department’s approximately 20 staff members had been fielding threatening letters, disparaging remarks on social media, and protests from members of the public angry about COVID-19 health restrictions in this south central Washington county. Meanwhile, they were working overtime and weekends trying to keep its 23,000 residents safe. Staff appeared demoralized and exhausted, but Quinn felt they had all developed a thick skin. Then, on June 17, 2021, she clicked on a “manifesto” from county Sheriff Bob Songer on his office’s Facebook page.

“This Office will arrest, detain, and recommend prosecution of any government official or agent thereof who knowingly and deliberately violates the rights of the people,” the post stated.

His definition of a “violation” included mandates from the public health agency for people “to wear or not wear any medical device they may choose to wear or not wear,” and “enforcement of mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations,” according to the post.

It was enough to make Quinn seriously consider giving up her more than a decade-long career in public health. Here she was working countless hours trying to fight a global pandemic with bare-bones resources. Instead of having support of the authorities meant to back her up, she was leaving her staff detailed information about her whereabouts, worrying that sheriff’s deputies might arrest her for doing her job.

“You just get to the point where you’re wondering if it’s worth the stress,” Quinn recalled thinking.

Over the past 3 years, COVID-19 has killed more than 1 million Americans, sickened at least 124 million more, and induced an immeasurable amount of trauma across all segments of society. Experiencing the blunt force of that trauma are people on the front lines of the country’s public health response — local and state public health workers like Quinn, sent into battle against a ravaging virus, often poorly armed and buffeted by toxic headwinds of incoherent messaging, misinformation, and political attack.

But as the fog of war begins to lift, people who work in public health are finally getting a chance to breathe, assess the damage, and consider ways to reimagine the system. What happens next will depend on America’s willingness to learn from the mistakes and challenges of the pandemic, experts said.

“The pandemic has highlighted both the strength and the challenges facing public health as a field,” said Josh Sharfstein, MD, vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. “There was an enormous amount of work done to protect people, and true heroism from a lot of people in the field. At the same time, it became obvious very quickly that public health is based on a pretty weak foundation in this country. We have not invested in the infrastructure, data, or the workforce, or laboratories that we need to tackle major problems, let alone a once-in-a-century pandemic.”

A Workforce Under Attack

When Quinn first started working for Klickitat County as an entry-level nurse in 2006, most people she met didn’t know the county had a public health department. Like many of her counterparts at the approximately 3000 other local public health agencies across the country, her office toiled in quiet anonymity, responding to small outbreaks of diseases such as tuberculosis or E coli, offering immunizations, and ensuring local businesses complied with health and safety regulations.

“In general, the population had no idea that we existed,” said Quinn. “Without the pandemic, (they) probably would have lived and died without ever having had any opinion one way or another about how we did business.”

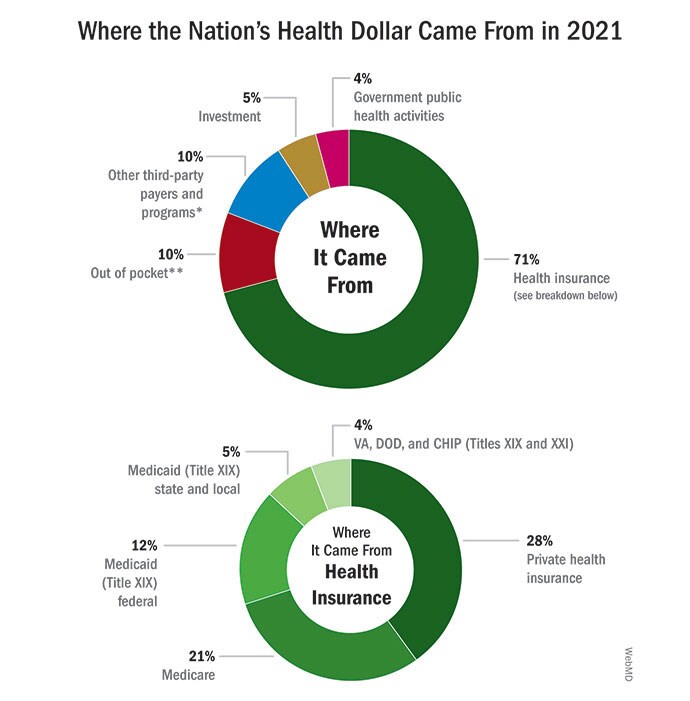

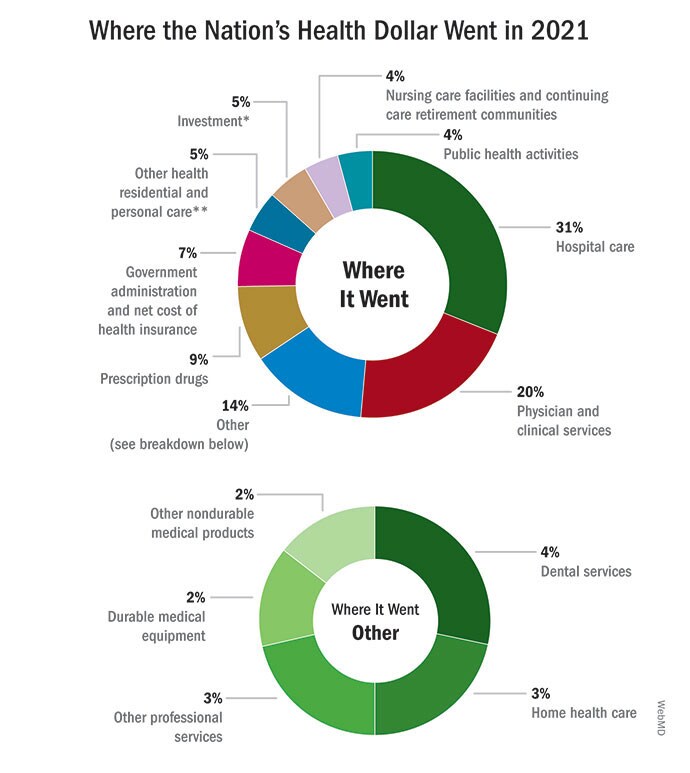

That lack of interest reflected a nationwide indifference and was accompanied by a lack of investment. In 2021, America spent a whopping $4.3 trillion on healthcare overall, of which public health received just 4%.

Decades of underfunding, especially following the Great Recession, meant that local and state public health departments were saddled with outdated technology and computer systems, some relying on fax machines to send and receive crucial information. As of the most recent count, the country needed an additional 80,000 public health staff to function properly, positions difficult to fill because of a lack of funding and low wages compared to the private health sector. This state of neglect left the nation’s public health system without the tools to respond to a potent regional or nationwide threat on the scale of COVID-19.

Even so, when COVID-19 struck, experts said that local public health departments rose to the occasion as best they could — often joined by enthusiastic new recruits from other government or health fields eager to play a role in fending off the microbial attacker. But enthusiasm wasn’t enough to overcome the system’s long-standing structural shortcomings. That, along with the grueling workload brought on by the pandemic and the sudden thrusting of public health officials into a contentious political spotlight, led to a rush to leave the field.

By September 2021, more than 300 state and local health officials had resigned, retired, or been fired, according to a Kaiser Health News (KHN) and Associated Press report. Burnout was rife. Many reported suffering threats, Harassment, and intimidation. Among the many examples was Ohio’s former state health director, Amy Acton, MD, MPH, who resigned after months of pressure from Republican lawmakers and the appearance of armed protesters outside her house. In California’s Orange County, chief health officer Nichole Quick, MD, MPH quit shortly after someone made a death threat against her during a county Board of Supervisors meeting. Emily Brown, MPH, director of the Rio Grande County Public Health Department in rural Colorado, was fired after disagreeing with county commissioners over reopening recommendations.

Experts have called the exodus of public health officials the largest in US history, according to the KHN/AP story.

Dr Anne Zink

“They’re exhausted, they’re tired,” said Anne Zink, MD, president of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and chief medical officer for the Alaska Department of Health. “They sacrificed everything for their neighbors and their families and the people that they were serving.”

Antiquated infrastructure is another challenged piece of the public health puzzle. Once again, policymakers tend to overlook public health when it comes to healthcare investments. After passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 under President Obama, the US poured $38 billion into incentivizing private hospitals and healthcare systems to modernize their data infrastructure. But that spending largely excluded public health.

When the pandemic required public health departments to track the virus in real time and mount a tailored response, their data collection and sharing systems were woefully inadequate. Computer systems didn’t talk to one another. Information had to be typed in by hand, sent via fax or email, or communicated over the phone. Key demographic data points were missing. Embarrassingly, officials said, the US ended up relying on other countries for critical data about the emergence of new variants and vaccine effectiveness.

Rebuilding the public health workforce and modernizing its data systems will take time and money. Since the start of the pandemic, the US government has poured billions of dollars into the public health response, including $3.2 billion to help state, local, and territorial jurisdictions across the country to strengthen their public health workforce and infrastructure, another $2 billion for public health hiring, and $200 million for data modernization. However, this is largely one-time, emergency funding. Many experts worry it won’t be enough to overcome years of underinvestment or be sustained long enough to stabilize the flailing system. It will also be hard to replace the loss of experience as people in leadership positions have left, experts said.

“COVID response funding provided by Congress buoyed our underfunded public health system and enabled a short-term surge in capacity to respond to the crisis,” Kerry Allen, director of government affairs at the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), said in an emailed statement. “But as a nation, we have chronically underinvested in public health, leaving our whole system underprepared to respond to daily challenges and emerging issues.”

Quinn, the Klickitat County, Washington public health director, said she remembers her department receiving an influx of cash during the H1N1 or “swine flu” epidemic in 2009, which paid for new computers and staffing. She was among those laid off when the money ran out. She worries the same will happen with the COVID funding her department received, once the pandemic fades from the headlines. If that happens, “we’re going to end up in the exact same place we were in COVID, which is a department that doesn’t have adequate resources to do the training, to do the preparation, to do this all over again,” she said.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have recommended training public health officials on how to respond to political and societal conflict, improving professional and employee support, and establishing systems for reporting and responding to harassment. Earlier this year, The US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, called for better working conditions, mental health support, and protection against violence as necessary measures to address burnout among the nation’s healthcare workforce.

Dr Vivek Murthy

“COVID-19 has been a uniquely traumatic experience for the health workforce and for their families, pushing them past their breaking point,” he said in a statement. “Now, we owe them a debt of gratitude and action. And if we fail to act, we will place our nation’s health at risk.”

Legislation to improve protections for healthcare and social workers against workplace violence is currently pending a vote in the Senate, although the bill does not specifically include public health workers. Public health workers were also left out of a 2021 directive from US Attorney General Merrick Garland to federal authorities to address increased risk of violence and harassment against school personnel. Allen said Garland did not respond to a letter from NACCHO urging him to rectify this.

Meanwhile, some individual states including California and Colorado have passed protections for public health and health workers, mostly to penalize “doxing” — the sharing of personal information about these workers online. Allen said the organization would welcome more legislation at the federal level to protect public health workers.

Communication Challenges

There was a time at the Oklahoma City-County Health Department when employees barely checked the agency’s social media feeds. That changed in 2020, when monitoring social media comments responding to county guidelines on masking and social distancing became a 24/7 job requiring staff to constantly remove or counter misinformation posted by the public. It didn’t help that the CDC was coming out with mixed messages about masks and the state of the pandemic, or that then-President Trump was promoting dangerous, unproven cures for COVID-19, or that Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt was vehemently opposing COVID-19 safety measures.

Dr Patrick McGough

“There were lots of people throughout the country and within the state of Oklahoma, too, that ended up in leadership roles in public health that had little experience and maybe little education toward it,” said Patrick McGough, DNP, MSHR, chief executive officer and public health officer for the Oklahoma City-County Health Department. “That really led us down some pretty dark paths a few times.”

In Florida, then-state health officer Scott Rivkees, MD, said he watched in alarm as initial success combating COVID-19 gave way to a flood of infections caused by people rejecting immunizations during the Delta variant-surge in mid-2021 because of widespread anti-vaccine rhetoric.

“It was very frustrating and very sad for us to see individuals becoming infected, developing severe COVID, passing away from what really is an illness in which severe disease is vaccine-preventable,” Rivkees said.

In Dallas, Texas, meanwhile, county Health and Human Services Director Phil Huang, MD, MPH, went on local television in early 2021 to advise the public against discarding COVID-19 precautions, even as Gov. Greg Abbott announced he was lifting a statewide mask mandate and allowing businesses to fully reopen despite substantial spread of the virus.

These scenarios highlight the difficulties of effective public health messaging in the pandemic’s highly politicized environment. Not even the president and the country’s top infectious disease expert, Anthony Fauci, MD, seemed able to agree on a focused pandemic response. Mask and vaccine mandates became a rallying cry for conservative angst about government overreach, and confusion and fear about the virus and vaccines provided ample fodder for online misinformation and conspiracy theories.

On top of that, public health officials were presented with the formidable task of informing and guiding the public on an illness they themselves were still struggling to understand. That lack of knowledge, experts said, resulted in innumerable communication blunders from the get-go that fueled public confusion, anger, and distrust, including the CDC’s conflicting stance on mask wearing, an overblown focus on the possible danger of outdoor transmission, and changing information about the safety of certain vaccines. This disjointed political and public response to the pandemic resulted in at least 318,000 unnecessary deaths from COVID-19, according to researchers at Brown School of Public Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Microsoft AI for Health.

Moving forward, said Robert Kim-Farley, MD, MPH professor at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health in Los Angeles, public health officials must learn to communicate more clearly to the public — preempting misinformation and confusion by explaining that guidance may change over time because both the virus and scientific understanding of it are evolving. These communication efforts will require input from social, behavioral, and political scientists, who are trained to understand human behavior and the environment into which messages are being communicated, he said. Public health must also learn to proactively use social media to get ahead of misinformation, he added.

Overcoming the politicization of pandemic information can’t fall solely on the shoulders of public health officials, however, said Johns Hopkins’ Sharfstein. He and other experts insisted that political leaders need to work with and better support their public health departments.

“The biggest challenge is the level of polarization and distrust in the country, and if that continues it will be hard for public health under any circumstances,” Sharfstein said. “This is not a problem that public health can solve alone.”

Partnering With Communities

Trust between the public health establishment and the people it serves has eroded on the national level — but groups with strong local ties have proven more resilient. In Oklahoma City, for example, the City-County Health Department had spent years building relationships with local businesses, schools, hospitals, churches, and community leaders through a coalition called Wellness Now, which focused on improving community health, and also through an emergency preparedness program called Push Partners that mobilizes local organizations to assist public health officials in responding to natural disasters and disease threats.

Although it didn’t eliminate criticism from the public during the pandemic, these relationships did make it easier to get local businesses and other entities to cooperate with public health orders, and allowed the department to lean on community partners for help with everything from finding extra storage for medical equipment to providing sites for vaccination drives, McGough said.

“We were on the phone talking to these folks,” said Phil Maytubby, deputy CEO and deputy health officer at the city-county health department. “So we were dealing with the motel/hotel association or restaurant group and we were explaining to them what and why. They may not have completely agreed with us but they couldn’t argue with what we had to say…We didn’t have to develop the trust. It was already there.”

A best practice to improve communication and build public trust is for public health departments to engage with different segments of the community in assessing and responding to health challenges, said Paul Kuehnert, DNP, RN, president and CEO of the Public Health Accreditation Board. The organization provides guidance and accreditation to public health departments across the country.

Kuehnert said departments that did this engagement prior to the pandemic tended to have more success getting the public on board with health guidelines and were more effective at reaching diverse communities especially vulnerable to the virus. That’s because they’d already developed trust with these groups before the pandemic hit, he said.

Veronica Halloway

In Illinois, the Department of Public Health had long ago created a Center for Minority Health Services division to address health disparities among certain populations. Veronica Halloway, MAS, who joined the center in 2005 and now leads it, said the division spent years engaging with grassroots groups to understand health problems and barriers affecting their communities and develop tailored messaging, such as to encourage HIV testing among Black youth.

During the pandemic, her department drew on these relationships to establish a COVID-19 equity task force that hosted listening sessions with community leaders, including from Black and Latinx communities, and used the input to develop guidelines for vaccine distribution and communication with different groups such as migrant farm workers, the deaf and hard of hearing, and people in rural areas.

“When you are at the same level as the people you’re trying to serve and you’re trying to understand and not second-guessing what the challenges are, it’s gratifying and you’re being a more effective leader,” said Halloway. “You really need to engage communities from the get-go. You can’t wait until there’s a pandemic to build those relationships and build that trust.”

Baltimore, meanwhile, partnered early on with local hospitals, health Systems, and the Maryland state government as well as philanthropic groups to bolster its response to the pandemic. The city fared better than many similar counties at avoiding sickness and death and in achieving high levels of vaccine coverage during the first year and a half of the pandemic, a study by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health found.

Experts cited numerous other lessons to build on from the pandemic, including a need to better address social determinants of health such as exposure to poverty, childhood trauma and environmental stressors; improve access to health care; strengthen the country’s disease surveillance system; and ensure sufficient stockpiles of ventilators and other supplies for emergencies.

Dr Mike Reid

Mike Reid, MD, director of the Center for Pandemic Preparedness and Response at the Institute for Global Health Sciences at the University of California San Francisco, suggested private health systems be given greater responsibility for responding to public health issues among their patients, so that public health departments can focus on the most vulnerable.

Fundamentally, political leaders and the public need to understand that public health is central to the country’s well-being and treat it accordingly, said Kuehnert.

“Public health is so core to the functioning of the society. It’s what we need to be able to be successful in every other aspect of our lives,” Kuehnert said. “It really does need to be seen as akin to transportation infrastructure, roads, public safety, national defense. And I don’t think we’ve seen it that way. I think that’s what the pandemic has really taught us — it’s a huge wakeup call.”

A New Generation

That call has apparently been heard by the generation now being trained in public health, with an unexpected surge of interest from students planning to enter the field. Several universities including UCLA and Johns Hopkins reported unprecedented applications for public health degree programs during the heart of the pandemic. UCLA is launching an undergraduate degree in public health after applications to its graduate programs increased by about a third, said UCLA professor Kim-Farley.

Meanwhile, a California Department of Public Health training and job placement program for early-career public health professionals was slammed with almost 900 applications for 45 positions after it launched early in the pandemic, said UCSF’s Reid.

COVID-19 has raised the profile of public health, sparking interest in a previously overlooked field, educators said. Many young people have recognized the potential for public health to make a difference in their communities.

“Even though there’s been controversy, it’s raised the level of awareness of what is public health in a lot of younger people’s minds,” said Kim-Farley. “Public health as a profession is something that is at least being put on people’s radar screens that they might not otherwise have thought about in the past.”

Johns Hopkins’ Sharfstein said the enthusiasm he hears from students entering the field has been a welcome contrast to the calls he got during the pandemic from frazzled public health officials he knows already working in the field.

“Our students are brimming with enthusiasm and optimism for the future,” he said. “They understand the challenges out there, but they’re ready to take those challenges on.”

Gina Naam

Among those students is Gina Naam, a PhD candidate at UCLA. She knew she wanted to study epidemiology before the pandemic, but living through the crisis has her considering taking a job at a government public health agency rather than sticking to academia, as she originally planned.

“I had read about [pandemics] in books, but I’d never really experienced it,” she said. “It’s made me appreciate [the public health field] more and see how important it is.”

Aisha Fletcher

Aisha Fletcher, a second year PhD student at UCLA, said she wants to help educate the next generation of public health professionals. Her research focuses on the impacts of structural racism on people’s health, a connection made widely apparent by disparities in infection and death rates during the pandemic. She works with undergraduate students in other programs of study as a teaching assistant, and said they now talk about that connection too.

“The pandemic has really highlighted to individuals outside of public health the importance of this work,” she said. “I was so excited that people finally understood that, ‘OK, health does not exist in a bubble.’ ”

Harnessing this enthusiasm and retaining students in the public health workforce is the next challenge, experts said. While it’s unlikely that public health work can outcompete the private sector in terms of salaries, governments could offer other types of incentives such as student loan forgiveness, said Adriane Casalotti, MSW, MPH, chief of public and government affairs for NACCHO. The organization has supported legislation to provide up to $35,000 in student loan repayment assistance for each year of service to a state, local, or tribal public health department, a model that already exists for medical school graduates who begin their practice in underserved areas.

And there are plenty of public health challenges ahead, from ongoing disease threats to climate change-fueled natural disasters to breakthrough cases of vaccine-preventable illnesses like measles. Chronic diseases, sexually transmitted infections, drug overdoses, and mental health trends also threaten social stability and well-being, experts said.

At the same time, advocates have pointed to recent US Supreme Court decisions on abortion, vaccine mandates, access to guns, and policies to fight climate change as undermining public health and the public health system. For example, the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2022 to limit the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate carbon emissions from power plants was a “setback” for local and state public health efforts, said Chelsea Gridley-Smith, NACCHO’s director of environmental health.

Zink, the Alaska Department of Health’s CMO, said public health priorities must be integrated into policymaking around healthcare in general. She suggested closer coordination between federal health agencies such as the CDC and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as certain federal funding to hospitals and clinics could be contingent on their contributing to public health priorities. They could be required to share data with public health departments on infectious disease rates, emergency room visits, and hospital bed capacity. Above all, public health departments will require ongoing, sustained funding to do their jobs effectively, she and others said.

“If we don’t want to spend 20% of our GDP on healthcare and have some of the worst outcomes [in the world], we have got to braid public health and healthcare back together,” Zink said. “To spend this much on healthcare and to not lead the world in being able to respond [effectively to public health threats], I think is a travesty.”

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a California-based journalist who writes on healthcare issues for publications throughout the state. She is a two-time USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellow and a former Inter American Press Association fellow.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article