Major depressive disorders are characterized by a significant health burden, including changes in appetite and body weight. Identifying biomarkers such as changes in brain function to treat depression is difficult due to the varying symptomatology of affected individuals. However, a research team—led by Prof. Dr. Nils Kroemer of the University Hospital Tübingen as well as the University Hospital Bonn (UKB) and the University of Bonn investigated whether conclusions can be drawn about the direction of appetite changes—increase or decrease—based on the functional architecture of the reward system in the brain. The results are now published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

Depression has many faces. A variety of changes in motivation, emotions and physical experiences characterize the disorder. Many patients suffering from depression do not only lose their drive and interest in rewarding activities, but also their appetite. At the same time, other patients report increased appetite during a depressive episode. So far, not much is known about the causes of these differences in symptoms within depression and how they can be specifically treated.

A team of researchers led by Prof. Dr. Nils Kroemer, who works in the Translational Psychiatry Unit of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital Tübingen and, since 2022, also as Professor of Medical Psychology at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital Bonn, has now been able to gain new insights into this topic as part of a multicenter study. By using magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers showed that the direction of appetite changes associated with depression is linked to specific changes in the brain’s reward system.

For a long time, scientists like Prof. Kroemer’s team have been searching for shared alterations in the reward system across patients with depression. This idea is intuitive because patients with depression usually experience striking changes in their motivation. “But the idea of a ‘depressed’ reward system seems to be more of an illusion,” explains Kroemer, the study’s lead author. “Instead of looking for general changes in the reward system, we can better relate specific changes, such as in appetite and body weight, to differences in the brain that help explain individual symptoms.”

About the study

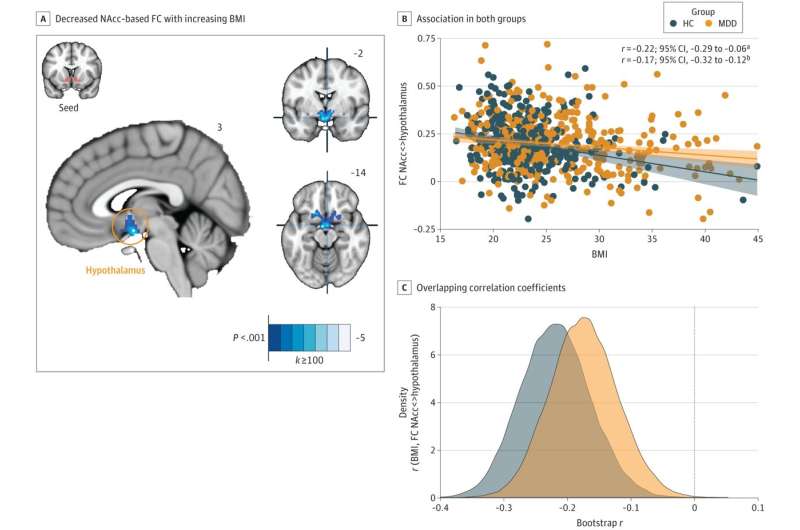

The team, consisting of researchers from several German university hospitals, examined the brain function of affected participants at rest and recorded their psychological symptoms. This allowed them to compare whether individual symptoms of depression are more predictable. To do this, they focused on the functional connectivity (also called connection strength; it describes the strength of communication between different brain regions) of the nucleus accumbens, one of the central regions in processing rewards and controlling goal-directed behavior, with other brain regions.

When patients with depression experienced a loss of appetite during a depressive episode, the strength of the connection between the reward system and other regions that play an essential role in value-based decisions and memory processes was reduced. If, on the other hand, there was an increase in appetite, the researchers observed a weaker connection between the reward system and the part of the brain where taste stimuli and bodily signals are processed. “These changes in the reward system were so prominent in severe depression that we were able to predict whether someone would suffer from an increase or loss of appetite based on the individual profiles of the reward system,” Kroemer said, describing the study results. “In contrast, it was not possible to tell whether someone had depression in general or not. So, it’s not just a change that matters, but especially the nature of the behavioral change.”

More targeted therapy options

Since there is no universal pattern of changes in the reward system in depression, the study points to the potential of precision medicine. These novel approaches do not focus on a general diagnosis but on individual symptoms. With the help of such symptom-based changes in the brain, it will be possible to develop more targeted therapies that directly address the specific symptoms of those affected in the future.

Source: Read Full Article