The human brain is bathed in a supportive fluid called the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that provides nutrients and is required for proper brain function. The composition of human CSF and how it is made are poorly understood due to a lack of experimental access. Madeline Lancaster’s group in the LMB’s Cell Biology Division has now developed a new brain organoid that produces CSF and has the potential to predict whether drugs can access the brain.

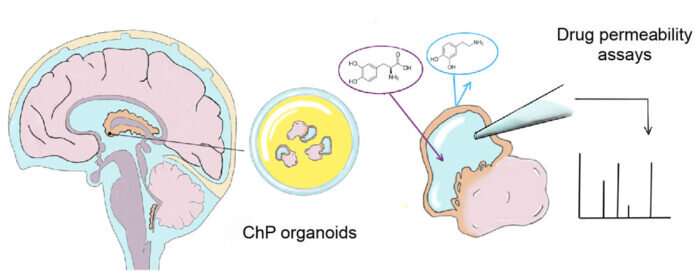

CSF is produced and secreted by a tissue found deep within the brain called the choroid plexus (ChP). The ChP also filters blood, acting as a barrier to most substances transported in the blood, while selectively permitting access of certain small molecules. To study the development and function of the human ChP, including how CSF is made, Madeline’s group developed a new organoid model of this tissue.

What are organoids?

Organoids are collections of organ-specific cell types that are produced from stem cells and can be studied as simplified miniature versions of organs. Organoids display similar organization of cell types to the organ they model and can perform some specific functions.

Scientists produce organoids by directing stem cells toward particular cell types through the use of signaling molecules, similarly to how the tissues would arise during development.

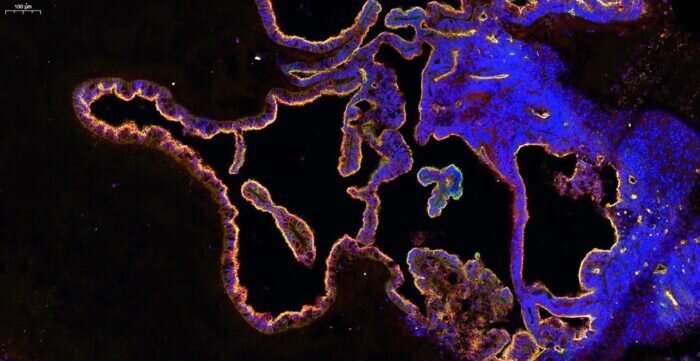

To develop a human-CSF-in-a-dish model, Laura Pellegrini from Lancaster’s group established a protocol to produce ChP organoids from human stem cells based on the group’s method for producing cerebral organoids. These organoids display key features of human ChP and develop CSF-filled compartments that are isolated from the surrounding culture media in which the organoids are grown.

The team found that this fluid contained known CSF biomarkers and they were able to observe changes in secretion of CSF components over time, as well as the distinct cell types contributing to these dynamic changes of CSF composition. Importantly, they discovered a previously unidentified cell type in the ChP: myoepithelial cells. These cells could be important in the generation of mechanical forces involved in CSF secretion.

The ChP organoids were also found to form a tight barrier exhibiting the same selectivity for small molecules as is seen for the ChP in the brain. For example, they prevented entry of the small molecule dopamine, but allowed transport of its precursor, L-Dopa. This demonstrates the accuracy of the model with regard to the tissue it represents, which means that ChP organoids could have predictive potential for the permeability of novel drugs. To demonstrate this, the team investigated one drug that recently failed in phase 1 clinical trials, BIA-10-2474, and report that the organoids could have predicted that the drug would inappropriately accumulate and cause neurotoxicity.

Source: Read Full Article