How TTP488 (azeliragon), an experimental drug, impairs aggressive, triple-negative breast cancer from metastasizing has been uncovered at the cellular level, according to researchers at Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center who worked in collaboration with scientists at the University of Miami, Florida. The finding appeared July 13, 2023, in Nature Breast Cancer.

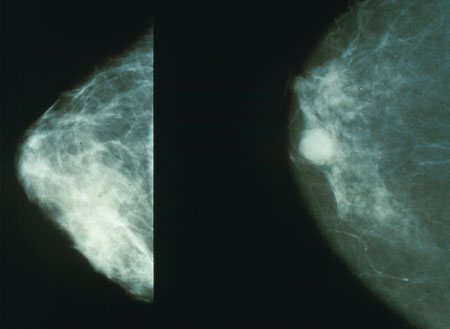

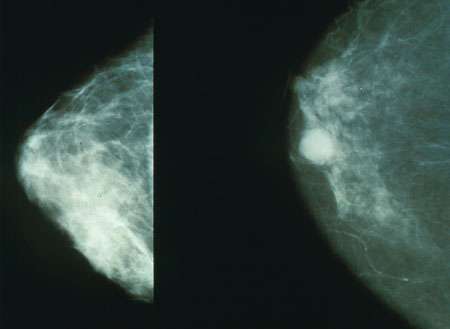

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) account for about 10–15% of all diagnosed breast cancers and are comprised of cancer cells that don’t have estrogen or progesterone receptors, nor do they produce a protein called HER2 in significant quantities. TNBC’s are more common in women younger than age 40 or those who are Black; for those cancers that metastasize, the five-year survival rate is only 12%.

TNBCs have eluded effective treatment for decades. This discovery pinpoints some of the signaling pathways and cellular mechanisms through which a receptor that sits on the surface of TNBC cells, called the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), regulates its deadly metastatic spread. Armed with this knowledge, the researchers were able to test the effectiveness of TTP488 in both the lab and in mice to show that the drug could be helpful in people.

“A clinical trial that is now underway at Lombardi and other cancer centers is a direct result of this preclinical research on RAGE inhibitors that started at the University of Miami and has continued with my move to Lombardi,” says Barry Hudson, Ph.D., associate professor of oncology at Georgetown Lombardi and corresponding author for this article.

“Our study is the first to show that TTP488 impairs breast cancer metastasis in cells and rodents. It is the only RAGE inhibitor that is approved for use in humans, so the implications for clinical trials are many-fold and we hope that progress against triple-negative breast cancers will be rapid.”

RAGE was discovered in 1992 as a possible factor involved in vascular complications of diabetes. It has subsequently been shown to be involved in a broad range of diseases due to its nefarious ability to bind many different molecules and induce inflammation.

Based on this knowledge, TTP488 was developed in the 2000s for Alzheimer’s disease, but trial results of the drug were equivocal. However, armed with more recent knowledge about its biology and effects, including its broad availability across many biological systems and its encouraging safety profile, it now appears to be a very promising candidate for clinical trials.

The investigators started their study by looking at two RAGE inhibitors: TTP488 and FPS-ZM1, both of which impaired spontaneous and experimental metastasis of TNBC in mice. But after extensive study in the lab and in mice, TTP488 was clearly the more effective drug and the one they pursued extensively enough to see if it qualified for use in people in a clinical trial. TTP488 still needs to be tested in larger, more advanced clinical trials to prove its true effectiveness so it is not yet available to women outside of those enrolled in clinical trials.

The investigators also identified three important pathways that could drive RAGE inhibition: Pyk2, STAT3, and Akt. This finding will help researchers better understand the mechanisms by which RAGE drives metastasis, potentially enabling combination therapeutic approaches targeting RAGE and these pathways.

“We are currently testing different combinations of TTP488 with other anti-cancer therapies to determine if RAGE inhibitors can synergize with those therapies,” says Hudson. “I think the outlook for effectively treating triple-negative breast cancers has become much brighter of late.”

More information:

Melinda Magna et al, RAGE inhibitor TTP488 (Azeliragon) suppresses metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer, npj Breast Cancer (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41523-023-00564-9

Journal information:

npj Breast Cancer

Source: Read Full Article